The Battle of Khe Sanh and a Story of Two Medal Hound Chaplains

There was little humor in the desperate battles to save Khe Sanh, but in other action two chaplains got more than they bargained for while chasing medals

Gerald “Jerry” Bijold was a 1st Lieutenant platoon leader in a company of helicopter gunships in an Army unit called an ARA for “Aerial Rocket Artillery.” He flew a UH-1 Huey B model gunship, similar to those flown by helicopter companies like the 170th and by the Pink Panthers before they transitioned to the Cobra in late 1968. Military unit naming can be confusing to non-military types like me. Airborne troops like the 101st were called that because when created as a unit they jumped out of airplanes. They were still called airborne in Vietnam when they arrived via Huey slicks, not parachutes. Artillery referred to big guns like howitzers fired at an enemy from a distance. Rockets were also considered artillery. So when they put rockets on helicopter gunships and used them like artillery to fire at enemy positions in offensive or defensive action, they became aerial rocket artillery.

Before being deployed to Vietnam in 1967, Jerry was commander of an artillery battery. After training as a helicopter pilot at Fort Rucker, he was a platoon leader in the 1st Cavalry Division Artillery. Cavalry? Doesn’t that sound like soldiers on horses? Now the horses were helicopters. This Division became famous in the Vietnam War during the Ia Drang Valley battle which was the first major engagement testing the airmobile concept. Both the US and North Vietnam learned important lessons that would serve as a primary basis for how the war was fought after that. This battle was made famous by the book We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, and by the Mel Gibson movie “We Were Soldiers.”

That was in 1965. When Lieutenant Bijold served in Vietnam the focus of attention was on Khe Sanh. It is still a name that lingers in the memory of those of us who lived back home with the distant war going on. All I remember of it was a bunch of brave Marines holding out against overwhelming enemy forces in a seige that seemed to go on forever. The American military interest in Khe Sanh began in 1964 and it served as an early launchpad for SOG insertions into enemy territory including into Laos. Khe Sanh is a little south of the Demilitarized Zone that separated North from South Vietnam, and General Westmoreland considered setting up a combat base there to be essential not just to interdict the ever-expanding Ho Chi Minh Trail, but as a base from which to launch major attacks against the North in Laos. That attack would come much later after US politics prevented US ground troops from going into “neutral” Laos and Cambodia. It was a South Vietnamese army operation and would result in the disastrous ARVN battle known as Lam Son 719.

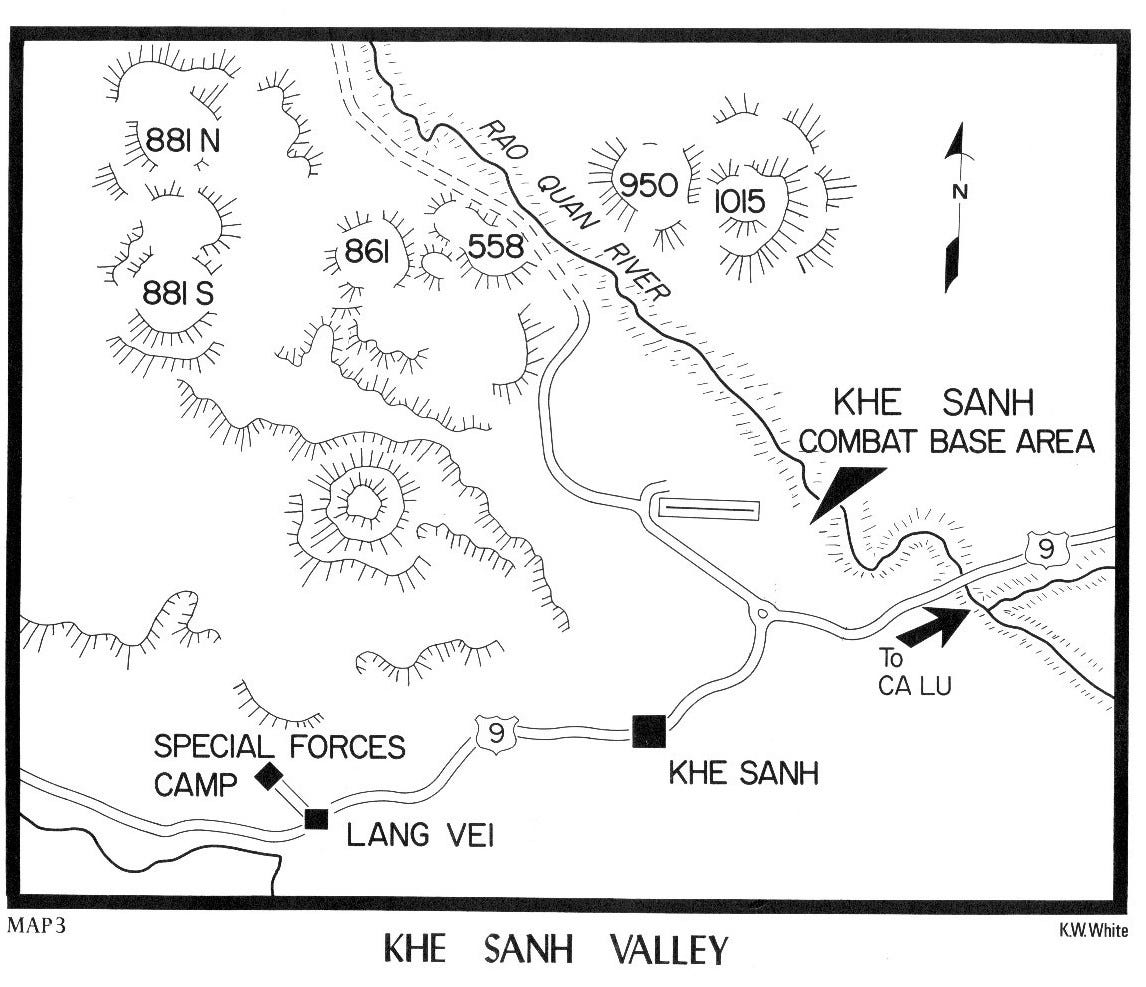

The attack against the Khe Sanh Marine base by the NVA began on January 21, 1968. This was nine days before the massive all-out attack by the NVA and combined VC forces known as the Tet Offensive. Westmoreland was convinced that the attacks of the Tet Offensive were a diversion to take US forces away from Khe Sanh. It still is a matter of debate. Preventing the enemy from taking Khe Sanh took on supreme importance. President Johnson was afraid it would prove another Dien Bien Phu, the battle that led to the ejection of the French from Vietnam. Westmoreland actively considered using tactical nuclear weapons, an option that was rejected due to practical problems like terrain. Much of the brutal fighting took place on the high peaks to the north and west of the combat base to prevent the NVA from using these to launch unending artillery and rocket fire on the embattled men in the base.

1st Lieutenant Bijold flew numerous missions supporting the US forces fighting against the relentless attacks by the North. His Huey B model gunship carried 48 2.75 inch rockets with ten pound warheads in two pods, one on each side of the gunship. His crew included a co-pilot firing the 4000 round per minute minigun, and a crew chief who manned the M60 machine gun from the helicopter's left door. He led a platoon of four gunships based at Ca Lu about 15 miles east of the combat base at Khe Sanh. Their mission was to support the troops on the ground and protect resupply and air assault missions carrying troops into the hot zones.

In an article in the Straphanger Gazette newsletter of the ARA Association, Bijold relates five memorable missions during March and April, 1968. On April 1 Westmoreland launched Operation Pegasus which was intended to relieve the seige and push the enemy away from the base. Bijold was flying lead with another gunship in his platoon, as they supported the extraction of a wounded Marine from near the base of Hill 881 (hills and mountains were named by the US military by their height in meters). The intense fire nearly made the extraction impossible, but the courage of the lead helicopter crew in getting the wounded Marine out resulted in a Silver Star for that crew. Bijold’s effective fire in support of the extraction resulted in his first of two Distinguished Flying Crosses.

In the second mission he reports that they were requested by an Army artillery battery under attack from an NVA tank. They fired rockets at the tank from a long distance and the tank went into hiding. They couldn’t spot it to put more rockets on it or call in an airstrike. They did, however, capture an NVA soldier hiding in a bomb crater between the tank and the artillery base.

Rockets were hitting the Khe Sanh base and Bijold’s platoon was called to help find and eradicate them. Their location was unknown, but using his artillery experience he went looking for them where he would put their rocket tubes if he was doing the firing. His experience and intution paid off as he located them just across the border in Laos along a mountain ridge. He kept far enough away to keep them from thinking they were spotted and called in air strikes. No “fast movers”, the A4 and F4 jets, were available so a B-52 bombing mission could be diverted if Bijold would identify the target and then do a BDA, bomb damage assessment. He agreed and ten minutes later the giant bombers unleashed hell on the rocket site. After about 15 secondary explosions, the rocket site was no more. Bijold reports that Khe Sanh had no more problems with rocket attacks after this mission.

In a particularly frustrating mission, Bijold responded to a call for help from a Marine infantry unit on the road about five miles west of Ca Lu, between Ca Lu and Khe Sanh. There was another Marine unit, with four tanks in the vicinity which Bijold and his team spotted. Bijold’s co-pilot spotted NVA with a B40 bazooka like rocket propelled grenade launcher. Bijold requested permission to fire at the enemy but it was denied as the infantry commander didn’t know for certain where all his men were. Even Bijold’s offer to mark the enemy location with smoke was denied. They watched as the NVA fired the RPG at the Marine tank forcing its evacuation with one Marine wounded.

The April 30 mission would prove to be Lieutenant Bijold’s last. The enemy was holding Hill 1015 north of Khe Sanh and from its promontory were attacking a nearby Marine unit. Bijold and his wingman rolled in from the south to attack the enemy position. As Bijold turned left out of the gun run to gain altitude for another run, they heard the “pom pom” of a dual anti-aircraft gun. His wingman saw where it was coming from in a valley between a couple of mountains and quickly diverted to attack it. In a moment it was destroyed. But the last two shells hit Bijolds gunship on the left side of the cockpit. One hit his foot pedal putting shrapnel into the front of his lower legs. A second shell hit his “chicken plate” chest protector with shrapnel entering his right earlobe and other shrapnel damaging his overhead console. His co-pilot had also been hit and there was blood in his left eye. He was squinting with his right eye watering. Bijold decided even with wounded legs and with little apparent bleeding, he could fly better than a mostly blind co-pilot. They made an emergency running landing back at Ca Lu and was met by two medics in a jeep. Soon he was in surgery at the hospital in Quang Tri and then medevaced back to the US for recovery.

The battle for Khe Sanh including the various battles to relieve it took the lives of 1000 to 3500 US soldiers with a great many more wounded. The number is uncertain as there were so many different conflicts involved it is difficult to say what belonged to Khe Sanh. After all that, the decision was made to abandon the combat base at Khe Sanh leaving the US public perplexed as to why so much effort was made to maintain it only to abandon it after victory was finally achieved at an enormous cost. The best estimates have about 5500 hundred NVA killed.

Before being sent to support the American and South Vietnamese defense of Khe Sanh, Lieutenant Bijold was in the An Loa district of south-central South Vietnam. As leader of an Aerial Rocket Artillery platoon, he and his crews supported combat operations in this area closer to Saigon. Here it was mostly VC they fought. Infantry would be inserted and extracted from locations where enemy were found. Much of it involved mortar patrols at night. The VC, hidden amidst the local population, would set up mortars at night to attack positions where they had found US and South Vietnamese forces. Mortar patrol usually made for a quiet night as the fights were sporadic and the VC didn’t typically have the large anti-aircraft guns that were found in the Central Highlands, Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam.

Bijold wrote in the Association newsletter that while in this area one evening two Army chaplains approached him. They asked if they could fly along with him. They explained they wanted to get an Air Medal, recognizing that it meant flying on 25 missions in the combat area. The Lieutenant explained that while often quiet, these missions could involve small arms fire hitting the gunship and a few nights before an AK-47 round had hit and damaged their rotor blade. It was also possible on these patrols to get called to provide fire support if troops on the ground got into a real fight with the enemy. They assured the platoon leader they understood and were willing to take the risk.

The Bong Son plain was a 30 mile long river valley with mountains on three sides. With the two brave chaplains onboard, the gunships began their mortar patrol on a clear night around midnight. About fifteen minutes into the patrol, a friendly unit came under intense attack near the base of one of the mountains. Bijold radioed for support from his wingship and turned to the fight. On the way he briefed the chaplains.

“We’ll be making steep rocket dives, followed by hard left turns. That’s to let our doorgunner fire his machine gun at the enemy. Expect heavy groundfire aimed at us.”

Bijold then made his first rocket run. By the time he lined up for his second run his wingship had arrived and they entered the racetrack gun run pattern so they could keep near continuous fire on the enemy. Enemy fire was heavy with green tracers reaching up to them as they entered and all the way through their run. Parachute flares were lighting up the battle which also illuminated the gunships as they made their rocket runs.

After the second dive to fire rockets at the enemy, Bijold turned to check on the chaplains. One was squeezing a rosary so hard he thought it would break. The other had a death grip on a small camouflaged Bible.

The runs continued until they were “winchester,” out of ordnance. They returned to base to rearm and refuel and once completed they were told to remain on standby for another fire support mission. That gave Bijold time to check in with his observers.

“I’ll write you up for your one hour of combat time. Twenty four to go,” he smiled.

“Thanks Lieutenant,” one said. “We’ve decided we don’t really need an Air Medal.”

“God bless you,” said the other. And they walked into the night.

(This is one of many great stories I am hearing as a result of writing It Was My Turn. In this case, Colonel Jerry Bijold (Ret) called me from Las Vegas to order a signed copy of the book. I started chatting about his service and he told me while he had essentially put the past behind him after retiring from the service, a couple of years ago he decided he would record some memories for his kids. Like many others at this time of their lives, I think Jerry is learning that others, and not just family, are indeed interested in their service. Also, as I have noted here several times before, I am more convinced than ever that sharing these stories is a very important part of the soul healing that is so necessary for these brave once-young men who served our country and all of us so well.

Jerry served the Army as a Field Artillery Battalion Executive Officer, retiring with numerous medals and awards including two DFCs, Purple Heart, five Meritorious Service Awards, 29 Air Medals and three Air Medals with V device for Valor. A Tardy Salute to Colonel Bijold!)