This is the story of Captain Keith Brandt, a US Army Cobra pilot from Bellingham, Washington. One of the great benefits of writing Terry Crump’s story, It Was My Turn, is getting to know in person, by phone or email, a considerable number of Vietnam veterans, especially aviators. This story comes to you from one of the most helpful I’ve met, Phil Marshall. Phil is the book review editor for the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association magazine Aviator. He was a Dustoff (medical evacuation helicopter pilot) with a great many very dangerous missions and is a remarkably prolific collector of amazing rescues by other Dustoff, slick, and gunship pilots and their crews. Marshall has written 21 books containing over 425 stories of rescues.

He generously sent me a few books and confronted with this overwhelming information, I asked him if he could point me to stories of any local heroes (northwest Washington State) and especially any SOG rescues. That’s how I came to find out about Keith Brandt.

It was mid-March, 1971. Lam Son 719 was winding down to its tragic conclusion. This was a large attack by the South Vietnamese forces to cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail by taking the Laotian town of Tchepone where the North Vietnamese Army was concentrated. Those who have read It Was My Turn will know that Terry Crump’s war was in support of the Special Forces teams, called SOG, who continually tried to hinder the supply of men and material from the North into South Vietnam on the Trail. The Cooper-Church Amendment halted US operations in Cambodia and Laos and Nixon was rapidly drawing down US ground forces. Lam Son 719 was supposed to prove to the North, the world, and especially the US war opponents that South Vietnam could hold back the North without the benefit of US ground troops. That attack into Laos would be totally South Vietnamese, except for massive US air power.

Terry expected to be called to support this attack with his Cobra, but he and other Panthers were needed for the continuing operations in II Corp, the area around Kontum and Pleiku. A great many other Hueys, Cobras, Loaches, and other US helicopters would be needed to aid the major assault. Over 750 helicopters took part in support of ARVN forces (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). They flew 160,000 sorties with some helicopters and crews flying many sorties in one day, as did Captain Brandt. 108 helicopters were lost, over 600 damaged, and about 120 of those damaged were beyond repair. Nineteen US Army aviators were killed, 59 wounded, and 11 missing. Keith Brandt and his co-pilot were among those killed.

The attack into Laos began in early February 1971 from the Khe Sanh area. ARVN forces did get to Tchepone in early March despite very heavy counterattacks, but then retreated and were hounded endlessly by an ever-increasing number of North Vietnamese (NVA) and Vietcong fighters. By March 18, the rout was on and ARVN forces were being evacuated from firebases and hot spots under attack by the North. US helicopters were now engaged not in assaults bringing troops in, but in desperate rescues of often panicked ARVN soldiers.

The ARVN 4/1 Battalion had 420 fighting men when they were inserted by helicopter into Laos at the start of the attack. On March 18, this unit was down to 88 men with 61 wounded. They were led by a Sergeant who could speak English and whose radio callsign was “Whiskey.” They were surrounded by NVA and trapped in a bomb crater at the base of a steep slope at 1500 feet. The NVA had loudspeakers calling for their surrender.

Sixty-eight US Air Force airstrikes helped keep the NVA away from the survivors. But, as the enemy closed in it was Army Cobras, led by Keith Brandt, that were needed to prevent the loss of the unit. Colored smoke grenades were used to mark their location so the Air Force strikes wouldn’t fall on them and so rescue helicopters could find them. But before the Hueys could get in to try and pick up those in the crater, they had used up all their grenades. Brandt and another Cobra from the D Company 101st Aviation Battalion, 101st Aviation Division, had flown numerous times to the crater, then back to Khe Sanh to refuel and rearm. Returning to the crater they pounded the pressing NVA with rockets, mini-guns, and grenades. In his front seat was Lieutenant Alan Boffman on his very first combat mission in the conflict.

Brandt, 31 years old, had a deep, rich voice and everyone on that mission recalls him radioing using his callsign Music One-Six. They may not have known the pilot, but his voice on the radio was memorable.

At about five pm Huey slicks from the 173rd Assault Helicopter Company from Lai Khe, fifty miles north of Saigon, responded to the call for help to extract the desperate survivors. Aviation units from all over South Vietnam were called in to help with Lam Son 719. Brandt offered to lead the rescuers in as he knew right where they were. Without smoke grenades, they identify their location to the pilots. He called on the radio:

“Spasm Two Two, this is Music One Six, follow me and I’ll lead you to the friendlies.”

Spasm Two Two was the callsign for the lead 173rd Huey known as the Robinhoods. Colonel John A. G. Klose (Ret) recalled what happened. Brandt led the lead slick toward the crater but as he approached with the slick following, he was hit with intense fire. Brandt radioed to abort the approach and he would lead them around for another try. But, his Cobra was on fire and his hydraulics were shot out, making the Cobra very difficult to control. As he turned his Cobra around in a slow 360-degree turn back toward the hopeful soldiers, he radioed:

“My mast is on fire and I’ve lost my hydraulics. There they are, 100 meters. I’m going to try and make it to the river.”

He knew he was going down, but his focus was on getting the rescue helicopter in to pick up the soldiers in the crater. His wingman and good friend Chief Warrant Officer Jack Hauck was flying nearby with 1st Lieutenant Butch Bates in his front seat as co-pilot/gunner. (Pictured above, Hauck on left) They accompanied Brandt and Boffman as they led the Robinhood slick toward the men in the crater. Their Cobra was hit about the same time as Brandt’s and a tail rotor gearbox chip detector light went on. That was serious trouble and Hauck knew he had to put the stricken bird down quickly. He headed toward the closest ARVN outpost which was also crowded with ARVN soldiers looking for rescue. It was an estimated 35 miles inside Laos.

His radio call for help was answered by a fellow 101st pilot flying a slick nearby. The slick was flying at about 4000 feet assigned to aircrew recovery duties. The pilot was Gerald (Gerry) Morgan, Kingsman 11, (pictured above) with only a few days left on his tour in Vietnam. (Tardy Salute readers may recall the remarkable story of Kingsman pilot Mike Ware who I had the great pleasure of meeting at the SOAR reunion. The Kingsman were B Company, 101st Aviation Battalion based at Camp Eagle.) Morgan’s co-pilot was Captain Willis Wulf. Morgan recalled that his crewchief Tim Durbin nonchalantly called on the intercom:

“There’s a Cobra going down on my side.”

Morgan followed Hauck’s Cobra down and hovered about ten feet off the ground. Hauck and Bates had to clamber onboard very quickly as almost immediately the helicopter was swarmed by South Vietnamese soldiers trying to get onboard. The door gunner pointed his gun at them and waved them off.

As soon as Hauck got on board he wanted to know about Brandt. Butch Bates, his co-pilot, had heard Brandt’s mayday call and that he was on fire and without hydraulics. He also heard Brandt’s last radio message:

“Never mind. We’re dead.”

Brandt’s collective was stuck and he couldn’t maintain rotor speed. Bates said the Cobra, engulfed in fire, dropped like a rock. The story with some differences was told in Keith Nolan’s book called Into Laos. He writes that Brandt’s last message was that he had lost his engine and his transmission was breaking up. Then:

“Goodbye. Send my love to my family.”

The version of events by Colonel Klose says his last words were “give my love to my wife and family.” Phil Marshall comments that since Butch Bates heard Brandt’s last transmissions, his version is probably the correct one. Brandt’s Cobra was seen to descend in flames and crash into the jungle, rolling onto its side. Everyone who saw it knew no one could survive.

The rescue of the ARVN soldiers in the crater went on. Many were hanging from the skids of the overloaded Hueys as they tried to lift off under intense fire. Many fell. Out of a unit of 420, there were 88 in the crater, but only 36 made it out safely to Khe Sanh.

There was much more action for the brave helicopter crews in the days to come as the defeated ARVN soldiers desperately fought off the determined enemy, hoping all the while for the distant whomp whomp sound of Hueys and Cobras coming to their rescue. On March 20, two days after the loss of Brandt and Boffman, the Commanding Officer of the Kingsmen, Major Jack L. Barker, was shot down and killed with his entire crew while attempting more ARVN rescues in Laos. Nine Kingsmen Hueys would leave Khe Sanh into Laos, seven would return.

Since Laos was off-limits to US ground troops, with the classified SOG warriors and some CIA operatives the only exceptions, recovering prisoners or bodies from Laos was essentially impossible. Laos said it held prisoners but none were returned. Nolan wrote the US government never negotiated for their return. Over 600 Americans were lost in Laos. Brandt and Boffman would remain in Laos until 1990.

In mid-January 1990, a joint US and Laotian team excavated Brandt’s crash site and recovered their remains. In October of that year, Jack Hauck was drinking his morning coffee and reading the newspaper when he came across a photo titled “Long-Awaited Farewell.” It told of the burial of Keith Brandt and Alan Boffman at Arlington National Cemetery. A year earlier Kingsman 11, Gerry Morgan, had contacted him. They would recall the day that Hauck’s friend Keith Brandt died and Morgan and his crew rescued Hauck and his Cobra co-pilot Butch Bates.

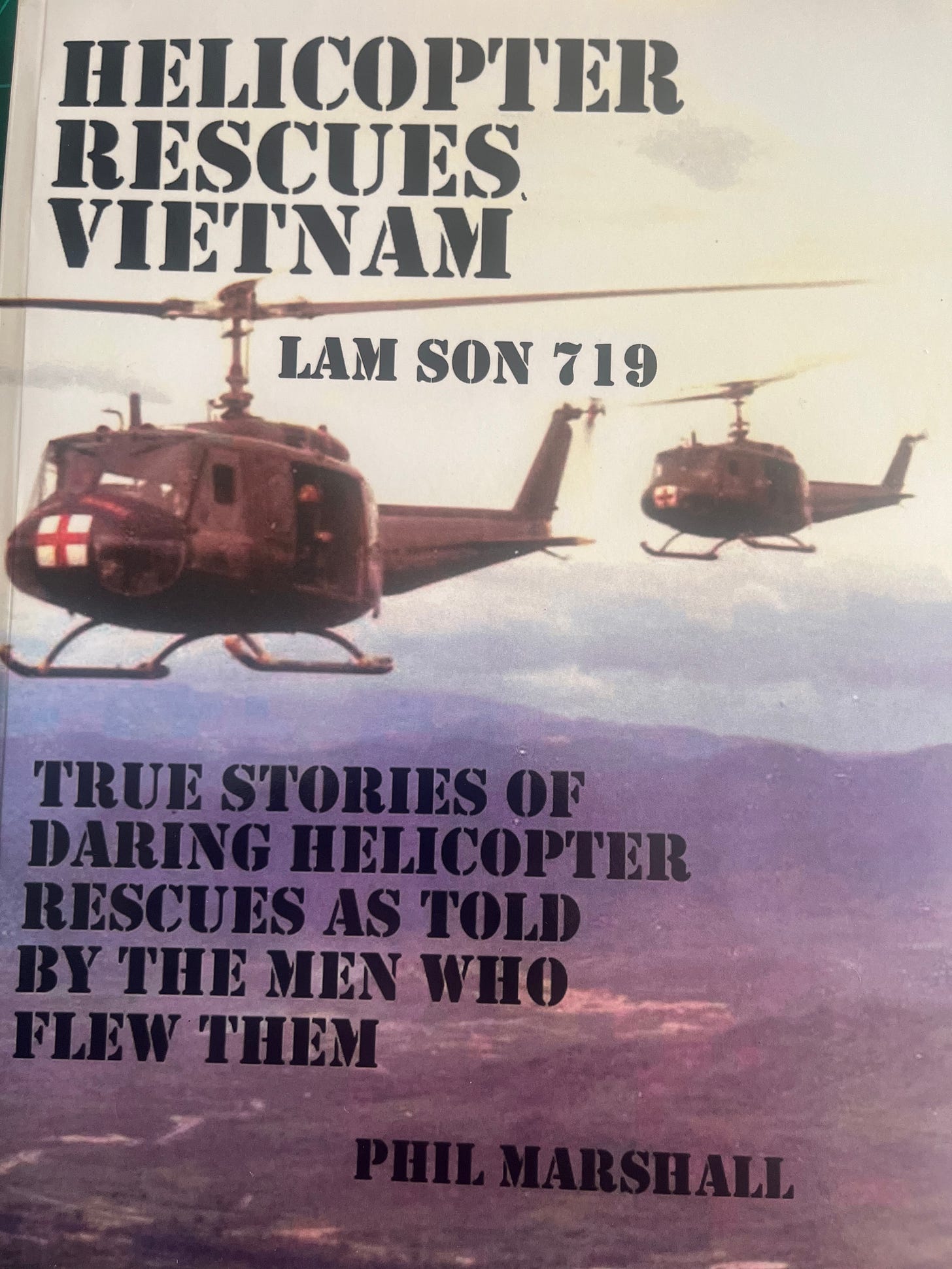

This story is found on several websites but most completely in Phil Marshall’s book Helicopter Rescues Vietnam: Lam Son 719. It is one of over 425 stories of helicopter rescues and that book is one of 21 written and published by Marshall. (Available on Amazon). Phil has been incredibly helpful to me in offering encouragement, additional resources and a very complimentary review in the current issue of VHPA’s Aviator magazine. I was very pleased to hear in a phone call with Phil today (Saturday) that he is now working on assembling helicopter rescues across the border supporting SOG.

Links re Captain Keith Brandt

http://www.armyaircrews.com/cobra_nam.html

https://www.pownetwork.org/bios/b/b398.htm

https://www.vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/5377/KEITH-A-BRANDT/

For those interested, I’ve added a new section to the website for It Was My Turn with information about the 361st Pink Panthers. It’s just a start with much more to come. It has the recent interview with Col Bill Reeder (Ret) and his time with the Panthers.

Ger, you've entered this new phase of your writing life with passion! No intellectual abstractions here, but raw realities of war and those who fought and lived or died.

Consuming and heavy, isn't it. And with many new relationships, deeply humanizing, I think.